INTRODUCTION.

SOME ACCOUNT OF AFRICA.

The continent of Africa forms one of the four quarters of the world. Its length from north to south is about 5000 miles, and its greatest breadth, from east to west, is about 4000 miles. It is separated from Europe by the Mediterranean Sea, and from Asia by the Red Sea. It has two grand divisions, North and South Africa; North Africa being that which lies north of the equator.--The greater part, of this continent, lies under a vertical sun, that is, the sun shines directly down upon it. Within the tropics, (the middle part of Africa,) the natives are generally jet black, and to the north or south they are generally of a dark olive colour. No natives, of a white complexion, are to be found in the whole of that great continent; the first time a person of that complexion appears in any of the African countries, he is an object of great terror and horror to the natives, especially to the women and children, who immediately run away from him.

Snow and ice are utterly unknown to most of its inhabitants; indeed they would as soon expect to see the hardest rock dissolve, or melt into water, as to see water changed into hard ice. One of the natives sailing in a ship to England some years ago, happened, when near England, to go hastily on deck on a frosty morning, and, for the first time, observing that his breath was like smoke proceeding from his throat, he was immediately seized with extreme horror, supposing there was a fire in his stomach, and ran to his master, who was asleep in the cabin, calling out fire! fire!

Ethiopia, (now called Abyssinia,) Egypt, and the countries bordering on the Mediterranean Sea, (now called the coast of Barbary,) all situated at the north part of Africa, were well known to very remote ages, but the immense regions beyond them, to the south, were entirely unknown till a few hundred years ago, when the Portuguese discovered the way to the East Indies by sailing round the Cape of Good Hope, which [sic] at the southern part of Africa.

SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF AFRICANER.

The father of Africaner, the subject of the present memoir, was a

Hottentot, born in the Hottentot country, now called the Colony of the Cape

of Good Hope. He, with his family, were in the service of a Dutch boor (or

farmer) in the district of Tulbach, and were employed in attending the farmer's

cattle. These, for the sake of pasture, when it was scarce in that dry and

sandy part of Africa, were sent higher up the country, beyond the limits

of the colony, to the vicinity of the Great Orange River, where, as in the

days of Abraham and Lot, the natives consider it no intrusion for strangers

to bring their flocks and feed them as long as they please. It is the same

in all the interior of Southern Africa that is yet known.

The father of Africaner, the subject of the present memoir, was a

Hottentot, born in the Hottentot country, now called the Colony of the Cape

of Good Hope. He, with his family, were in the service of a Dutch boor (or

farmer) in the district of Tulbach, and were employed in attending the farmer's

cattle. These, for the sake of pasture, when it was scarce in that dry and

sandy part of Africa, were sent higher up the country, beyond the limits

of the colony, to the vicinity of the Great Orange River, where, as in the

days of Abraham and Lot, the natives consider it no intrusion for strangers

to bring their flocks and feed them as long as they please. It is the same

in all the interior of Southern Africa that is yet known.

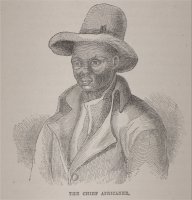

Image right: Jager Africaner as seen by Moffat in his book Scenes and Services in S Africa

Afterwards the family lived with another boor, named Piemaar, at a farm on the banks of the Elephants' River, which is the largest, except the Great Orange River, on the western side of South Africa, and in such a country may literally be called a river of life, for trees, grass, &c. for a little distance from its banks, look green, healthy, and lively, but beyond, all is a barren waste.

It was about this time that the Cape colony first came under the government of the English, by being captured from the Dutch. A report was circulated by evil-minded persons that all the Hottentots were to be forced to become soldiers, and to be sent out of Africa. This report made old Africaner, and his sons, resolve to retire beyond the bounds of the colony, to escape being forced into the army. However, they still continued in the service of Piemaar, the boor, who sometimes employed them on plundering expeditions against the defenceless natives of the interior, furnishing them with muskets and powder for that purpose. In this way they were taught to rob for their master, and thus, after a time, they learned to rob for themselves.

From some circumstances which occurred, suspicions arose in the minds of the old Hottentot, and his sons, that their employer acted unfaithfully to them during their absence and his sending them more frequently from home confirmed their suspicions; and they determined to refuse to leave home any more on such expeditions.

Information having come to Piemaar that the bushmen had carried off some cattle belonging to the district over which he was Field-cornet, (a kind of justice of peace,) he, in his official character, commanded them to pursue the Bushmen in order to re-capture the cattle. This order they positively refused to obey, saying that his only motive for sending them on such an expedition was that they might be killed.

Piemaar, being enraged by their resisting his order, proceeded to flog Jager, one of the sons, who seized his gun, which he fired at his master, and a serious scuffle ensued, in which Jager and Christian, killed not only Piemaar himself, but also his wife and child.

In consequence of this melancholy occurrence, the whole family, with some other Hottentots, immediately fled from the colony to Great Namacqualand, beyond the Great Orange River, where Christian Africaner became the chief of a party of marauders or robbers.

Having settled themselves in that country and being possessed of muskets and powder which had been carried off from their murdered master, they resolved upon an expedition against some part of the colony, to attack some boor's place, that might obtain more muskets and powder. In this expedition they murdered one Engelbrecht, a boor, and likewise a half Hottentot, from whom they carried off much cattle. At this time Africaner became the terror of the colony, in consequence of his boldness and success, and a thousand dollars were offered to any man that would shoot him.

Africaner was not satisfied with making incursions into the colony; he also attacked the neighbouring tribes of Namacquas, and plundered them of their cattle, which were the chief means of their subsistence. From his having fire arms, and from his intrepid conduct, he became the terror of the nations far and near. In some of his attacks upon the farmers in the colony, he was satisfied with their surrendering to him the muskets, powder, and lead, they had in their possession. In this way he obtained between thirty and forty muskets, which rendered him a formidable foe to nations whose only weapons of defence were spears, bows and arrows.

On the missionaries first arriving at Warm Bath, in North or Great Namacqualand, and commencing a missionary settlement there, Africaner, with his people, came and took up their residence near them, and for some time behaved in an orderly and peaceable manner; till a circumstance occurred which led to the complete ruin of the Missionary settlement there.

Africaner, and his brother Jager, dared not to visit Cape Town themselves, after the murders and plunders they had committed in the colony, and they were obliged to employ others to procure for them what they wanted from thence. On one occasion, about the beginning of the year 1811, they employed a man, named Hans Drayer, to purchase a wagon for them at the Cape, which is a vehicle of great value in such countries for travelling, &c. For this purpose they entrusted him with three span (or teams) of oxen, ten in each span: with two span he was to purchase the wagon, and with the third to bring the wagon home to Namacqualand. On his way to Cape Town, Hans met a boor to whom he was indebted for a considerable sum: for the payment of this debt the boor seized the whole of the oxen: and Hans was obliged to return to the Missionary station at Kamies Fountain, in Little Namacqualand, where he usually resided, and he refused to give to Africaner any satisfactory account of the oxen.--Africaner was so angry at his loss, and so exasperated against Hans, that he pursued him to Kamies, where he and his people put him to death, and committed great enormities.

Not long after this painful occurrence, the friends of Hans, with the assistance of some Namacquas, in their turn, attacked the kraal (or town) of Africaner: who, to be revenged upon the Namacquas for aiding the friends of Hans against him, afterwards fell upon their kraal. Finding themselves too weak to resist him, they implored assistance from the Namacquas at Warm Bath; who, complying with their request, sent out a large armed party to defend them. This conduct so enraged Africaner, that he threatened destructioned to the settlement at Warm Bath.

Under the apprehension of certain destruction from so resolute a savage, Mr. Albricht, the Missionary, and his wife, left that station, removing what goods they could, and burying the rest in the earth, in hope of returning at a future period; but the mission was never resumed; for, after enduring some fatiguing journeys, Mrs. Albricht (formely Miss Bergman, from Holland) died at silver fountain, in Little Namacqualand, as some thought, from a broken heart. After this Mr. Albricht took up his residence at Kamiesberg and Pella. He died not long after of a dropsy, probably occasioned by the bad water in that part of the country.

Africaner accomplished his threat, for he attacked the Namacquas at Warm Bath, and carried off a great number of their cattle, and continued to molest them till at length the Mission-house and the chapel were burnt, and the inhabitants of the village almost entirely dispersed, and most of them obliged to live upon roots, wild berries, and whatever they could find.

The succeeding year, viz. 1812, when the Rev. J. Campbell visited Africa, on the affairs of the London Missionary Society, he found it necessary to cross that continent from the eastern to the western side. During this journey, he found every town through which he passed well acquainted with the name of Africaner, and all trembling lest he should pay them a visit; he was the only person whom Mr. Campbell was afraid of meeting during this part of his journey. However, on arriving safe at the Missionary station of Pella, on the western side of Africa, he wrote a letter to Africaner, expressing regret that he should be the occasion of so much misery and oppression in that part of Africa--that as he knew there was a God, and a judgment to come, he stated his belief to Africaner that he must be an unhappy man by being the cause of so much unhappiness to others. And as the Word of God taught forgiveness, he offered to send a missionary to instruct him and his people, notwithstanding all he had done against the Missionary Institution at Warm Bath, if he expressed a desire to have one sent to him.

So great was the terror of both Namacquas and Bushmen at the name of Africaner, that though a present was to accompany the letter, and payment to be given to the bearer of it, a considerable time passed before a person could be found of sufficient courage to undertake it. Indeed, for a long time after these Namacquas had fled to Pella, across the Orange River, from the dread of Africaner, the least rising of dust or sand at a distance frightened them very much, and they were sure it was Africaner coming after them. At length, however, a person was obtained to carry the letter to Africaner, who was his relation, and who had crossed the continent with Mr. Campbell. Six years afterwards, when Africaner met Mr. Campbell at Cape Town, he said, "that the offer of a Missionary which the letter contained, made him glad--that in his heart he had long wished for a teacher--that his brother Jager, who could write, had written an answer, which was sent across to the Griqua country, and from thence to the colony, that it might proceed to Mr. Campbell at the Cape, desiring to see a Missionary, and that he might be an Englishmen." This letter never reached Cape Town.

Africaner receiving no answer from the Cape, sent a messenger to the Missionary station at Pella, in Little Namacqualand, about two days journey from his own kraal, requesting that the Missionary promised to him, might be sent as soon as possible. In consequence of which message, Mr. Ebner, one of the Missionaries at Pella, proceeded to Africaner's kraal, where he immediately commenced his labours. We are not acquainted with the particulars of what passed, but the preaching and conversation of this Missionary were blessed of God; for some time afterwards, Africaner expressed himself to the following effect:--

"I am glad that I am delivered. I have been long enough engaged in the service of the devil, but now I am free from his bondage. Jesus has delivered me; him will I serve, and with him will I abide."

Several other natives were converted to God, a Christian congregation was formed--and Africaner was taught to read the sacred scriptures, in which he took much pleasure.

The Missionary, Mr. Ebner, who first went to Africaner's kraal, after continuing there upwards of two years, returned to his former station, and was succeeded by Mr. Moffatt, who was instrumental in building up the new converts in their faith, and adding to their number, and maintaining peace amongst them. Indeed, from the day the gospel entered their kraal, they ceased to disturb the peace of the neighbouring tribes for, so far as the truths of that precious gospel are influential on the minds of men, they produce peace on earth, and love towards each other. The first effect of the gospel at the city of Lattakoo, towards the eastern side of Africa, was to dispose the king and chiefs of that nation to come to a public resolution, to go no more upon plundering expeditions against other tribes. Many of the converted heathens also in South Africa, have contributed very liberally of their little property, to assist in sending the gospel to other regions where it has not penetrated.

In the latter end of the year 1818, a deputation from the Missionary Society left England, on a visit to South Africa, where they arrived early in the next year. Soon after their arrival, Mr. Moffatt, accompanied by Africaner, from Namacqualand, also came to the Cape. The government being satisfied, from the statements of the Missionary, that a great change had taken place in the character of Africaner, passed by his former misdeeds in the colony, which happened while the colony was under the government of Holland. And, in order to secure his friendship to the colony, the importance of which was well known, the governor made him a present of an excellent wagon, which cost about eighty pounds sterling.

Africaner's appearance in Cape Town excited considerable attention, as his name and exploits had been familiar to many of its inhabitants for more than twenty years. Many were struck with the unexpected mildness and gentleness of his demeanour, and others with his piety and accurate knowledge of the scriptures. His New Testament was a cheering object of attention, it was so completely thumbed and worn by use.

Being asked what his views of God were before he enjoyed the benefit of Christian instruction, his reply was, that he never thought any thing at all on these subjects; that he thought about nothing but his cattle. He admitted that he had heard of God, but he at the same time stated, that his views of God were so erroneous, that the name suggested no more to his mind, than something that might be found in the form of an insect, or in the lid of a snuff-box.

As Mr. Moffatt, who had brought him to Cape Town was to join the Mission at the city of Lattakoo, Africaner was asked to attend to the instruction of his people himself, till the Missionary Society should be able to send out a teacher to supply the place of Mr. M. With great modesty and diffidence he gave his consent.

A friend in Cape Town when noticing to him the valuable present of a wagon, which the government had made to him, remarked that he must be very thankful for such a mark of their esteem.

"I am (said he) truly thankful to government for the favour they have done me in this instance; but favours of this nature to persons like me are heavy to bear. The farmers between this and Namacqualand, would much rather hear that I had been executed at Cape Town, than that I had received any mark of favour from government. This circumstance will, I fear, increase their hatred against me; under the influence of this spirit, every disturbance which may take place on the borders of the colony will be ascribed to me, and there is nothing I more dread, that that the government should suppose me capable of ingratitude."

Those were singular remarks from a man who, only six years before, had been the savage leader of a savage tribe, far from the residence of civilized men, and seeking to destroy them.

While halting for a few days at Tulbagh, a town sixty miles from Cape Town, on his return to his own country, Africaner was exposed to a severe trial of temper, which afforded an opportunity of showing his Christian spirit. A woman, under the influence of prejudice, excited by his former character, meeting him on the public street, followed him for some time, as Shimei followed King David, calling after him with all her might, and heaping upon him all the coarse and bad names which she could think of. Reaching the place where his people were standing by his wagon, with a number of persons whom this woman had drawn together still following him--his only remarks were--"This is hard to bear, but it is part of my cross, and I must take it up."

At Tulbagh, Africaner took an affectionate farewell of his missionary friend, Mr. Moffatt, who was on his way, with the deputation, to visit the Society's stations on the eastern coast of the colony; after which he was to proceed to Lattakoo, to assist in the Mission which had been for some time established in that city. Africaner travelled along the western side of the colony towards his own country, where he arrived in safety a few weeks after, to the great joy of his friends at home. This was the first time he had been entirely without a Missionary, since his conversion to Christianity. Now, the rule, and the religious instruction of his people, entirely devolved on himself. He, being by grace a humble man, felt it a weighty concern, and saw it necessary to look constantly to God for wisdom to direct and grace to support him, in fulfilling the duties connected with his double character of ruler and teacher.

He continued to labour amongst his people for about a year, when he believed Mr. Moffatt must by that time have taken up his residence at Lattakoo. He therefore resolved to pay him a visit, and carry with him, in his wagon, what books and furniture Mr. M. had left behind him at the kraal. This was a long journey across the continent, and a great part of it was over deep sand; but the season encouraged him, being June, which is the middle month in a South African winter, consequently the coolest season in the year. He reached Lattakoo in the middle of July, 1820, where he received a most hearty welcome from the Missionary brethren and sisters there, and he delivered, in good condition, the furniture and books which he had brought with him.

This kind service was done from gratitude and pure Christian affection towards the Missionary. It was indeed a rare instance of disinterested benevolence, as the journey to and from Lattakoo occupied full three months. He made no boast of it, and looked for no recompense. While remaining at Lattakoo, he conducted himself with much Christain meekness and propriety, and waited patiently till the deputation finally left that city.

He and his people made part of the caravan for upwards of an hundred miles, until they reached Berend's-Place, which is the town nearest to Lattakoo in the Griqua country: it chiefly belongs to Berend, an old Griqua chief. The meeting between Africaner and this chief was truly interesting, having not seen one another for four and twenty years, when at the head of their tribes they had fought for five days on the banks of the Great Orange River. Being now both converts to the faith of Christ, and having obtained mercy of the Lord, all their former animosities were laid aside, they saluted each other as friends, and friends of the gospel of Christ.

These chiefs, followed by their people, walked together to the tent, when all united in singing a hymn of praise to God, and listening to an address from the invitation of God to the ends of the earth to look to him , and to him alone , for salvation. After which the two chiefs knelt at the same stool, before the peaceful throne of the Redeemer; when Berend, the senior chief, offered up a prayer to God. The scene was highly interesting, they were like lions changed into lambs, their hatred and ferocity having been removed by the power of the gospel; indeed, when the Namacqua chief was converted, he sent a message to the Griqua chiefs, confessing the injuries he had done them in the days of his ignorance, and soliciting them at the same time, to unite with him in promoting universal peace among the different tribes.

The two chiefs were much together till the afternoon of the next day, when after taking an affecting farewell, Africaner with his wagon and people set off to the westward, in order to cross over to Namacqualand, and the rest of the caravan travelled south in the direction of Cape Town, from which they were distant about seven hundred miles.

On reaching home, Africaner again resumed the religious instructions of his people, and remained constantly with them till his final removal to the everlasting world.

How long his last illness continued we are not informed, but when he found his end approaching, like Joshua, he called all his people around him, and gave them directions concerning their future conduct.

"We are not," said he, "what we once were, savages , but men professing to be taught according to the gospel:

let us then do accordingly. Live peaceably with all men, if possible; and

if impossible, consult those who are placed over you, before you engage in

any thing. Remain together as you have done since I knew you; that when the

directors think fit to send you a Missionary, you may be ready to receive

him.

Behave to the teacher sent you, as one sent of God, as I have great hope

that God will bless you in this respect when I am gone to heaven. I feel

that I love God, and that he hath done much for me, of which I am totally

unworthy.

"My former life is stained with blood, but Jesus Christ has pardoned me, and I am going to heaven. O! beware of falling into the same evils into which I have led you frequently: but seek God, and he will be found of you, to direct you."

Soon after delivering the above address, he died in peace, a monument of redeeming mercy and grace.

From the time of his conversion to God, to the day of his death, he always conducted himself in his family and among his people, in a manner very honourable to his profession of Christianity; acting the part of the Christian parent, and Christian master.

While his people were without a Missionary, he continued with much humility, zeal, diligence, and prayer, to supply as much as in his power the place of a teacher. On the Lord's day he expounded to them the word of God, for which he was well fitted, having considerable natural talents; undissembled piety, and much experimental acquaintance with his Bible.

He had considerable influence among the different tribes of Namacquas, by whom he was surrounded, and was able to render great service to the missionary cause among them. He was also a man of undaunted courage, and although he himself was one of the first and severest persecutors of the Christian cause in that country, he would, had he lived, have spilt his blood, if necessary, for his Missionary.

CONCLUDING REFLECTIONS.

The history of a Christian Hottentot chief, will certainly be a novelty in an English juvenile library: indeed it is one of the singular occurrences of the extraordinary period in which we live.

No man cared for the soul of Africaner in the days of his youth. His father and friends were all heathens, and the boor in whose service they lived was little better, so that he was allowed to grow up in ignorance, like the wild beasts of the desert in which he lived; consequently, when he became a man, he was destitute of all good principle, fearing neither God nor man. From his avarice, cruelty, and ambition, he was for many years a scourge to the poor African tribes by which he was surrounded. At length, by means of the gospel of God coming to his country, he was deeply convinced of the error of his way; of the greatness of his guilt, and the dreadful punishment awaiting sin in the world to come; this led him to cry earnestly for mercy, through the atoning sacrifice of the Son of God.

God heard his prayer, and forgave his transgressions, on which he became a new man; relinquishing forever his former abominations, and devoting his life to the service of God and the benefit of his fellow-men. The first and last part of the life of the apostle Paul were not more opposite to each other, than that of Africaner's.

God's forgiveness of the sins of this noted African, is no encouragement to others to commit or to continue in sin, but it glorifies the riches of the grace of God, and ought to encourage the guilty to repair to the same fountain of life to which he went, and in which he was washed from all his aggravated stains. This fountain is the great atonement for sin made by Jesus Christ, when he willingly submitted to crucifixion on the cross at Calvary. To his cross let us also look, that we may not perish, but that we may have everlasting life. Let those who are favoured with religious instruction in the days of their youth, bless God for appointing their lot to be so different to that of Africaner, and millions more at present in the world. Remembering also that to whomsoever much is given, from them much will be required.

THE END.